Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Atlanta Economics Club

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Atlanta, Georgia

May 21, 2018

- Atlanta Fed president and CEO Raphael Bostic speaks at the Atlanta Economics Club's luncheon about the economy, his economic outlook, and the Fed's inflation target.

- Bostic: The economy is arguably as close to the Fed's employment and inflation goals as it's been over this expansion.

- Bostic continues to see the economy growing above potential this year, around 2 1/2 percent, and slowing to its longer-run growth rate of around 1 3/4 percent over the medium term.

- Bostic notes that an upside risk to his economic outlook is the prospect for capital spending given tax reform, while a downside risk is the uncertainty about changes in trade policy.

- Bostic asks if the current monetary policy framework is still the right one, noting that once monetary policy has normalized, the federal funds rate will settle at a level significantly below historical norms.

- Bostic explains that if the real rate of interest is likely to remain low, then giving the Fed enough room to fight even run-of-the-mill economic downturns requires boosting the nominal rate of interest.

- To increase the nominal rate, Bostic is drawn to a monetary policy framework that has a version of price-level targeting.

- Bostic believes a sound policy framework provides a credible nominal anchor while maintaining flexibility to address changing circumstances, and flexible price-level targeting can be a part of such a framework.

It's a pleasure to be with you today. I'm proud of the Bank's affiliation with the Atlanta Economics Club and am pleased to be able to provide a place for you to gather.

In my comments today, I'd like to share my latest view of the economy and my economic outlook. I'll also be sharing some thoughts on recent inflation performance and how I am thinking about the Fed's inflation target going forward. Before I begin, let me say that I am offering only my personal opinions today. I'm not speaking for anyone else in the Federal Reserve or for the Federal Open Market Committee, or FOMC.

Current economic conditions

Price stability is one part of the dual mandate given to us by Congress. Promoting maximum sustainable employment is the other half. From the perspective of that dual mandate, we're arguably as close to these goals as we've been over this expansion.

The unemployment rate has fallen to its lowest level since December of 2000. Broader measures of joblessness, like those that include people marginally attached to the labor force or those working part-time for economic reasons, have also improved.

Despite the dramatic improvement in the employment picture, overall wage growth remains tepid compared with previous expansions. That said, we have seen evidence of increasing wages along some dimensions consistent with improvement in labor utilization rates. For instance, if you look at the typical wage growth experience of individual workers, as the Atlanta Fed's Wage Growth Tracker does, it shows that the premium for workers who change jobs is at a cyclical high.

My staff spends a lot of time canvassing businesses in the Sixth District to assess whether the facts on the ground seem consistent with our read of things based on the official statistics. Feedback suggests, as the data show, that labor market conditions have tightened, though I wouldn't characterize the situation as overheated. This all leads me to conclude that the economy is close to or at "maximum employment" but not yet significantly beyond that point.

Turning to price stability, the other half of the FOMC's dual mandate, the Fed has determined that a 2 percent inflation rate, as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditures (or PCE) price index, is most consistent with the notion of stable prices. The year-over-year growth rate in headline PCE inflation has now hit this target, and the less-volatile core PCE measure is just a tenth of a percentage point shy of that mark.

This is a significant development considering that annualized inflation over this expansion—which is nearly nine years long now—has fallen short of the 2 percent goal by roughly half a percentage point. On top of the recent inflation reports that suggest we are currently very close to our target, my staff and I are beginning to discern a shift in sentiment among our contacts and in our survey data that, if anything, suggests some upward pressure on inflation.

Reports on likely pricing pressure going forward are mixed. Significant pricing power appears contained to businesses and sectors that are exposed to cost pressures associated with actual or potential tariffs. But today, these are isolated developments.

On balance, I view the economy as on track and believe we are close to mandate-consistent outcomes for both inflation and employment. Given that measured inflation is already effectively on target, I won't be surprised to see a modest overshoot of our longer-run target. In fact, my own forecast is that, even with further gradual removal of monetary policy accommodation, inflation is likely to run a bit above 2 percent for a while.

Economic outlook

So with those considerations in mind, allow me to share the Atlanta Fed's baseline outlook. I continue to see the economy growing above potential this year, in the neighborhood of 2 1/2 percent, and slowing to its longer-run growth rate of around 1 3/4 percent over the medium term.

One area to watch over the next year or so is how consumers respond to tax reform. To that end, I have received few, if any, reports of a noticeable acceleration in consumer spending attributable to the tax cuts. Retailers generally report steady sales growth overall, but our anecdotal reports are consistent with the survey data from the New York Fed indicating that consumer expectations on future spending growth are relatively flat.

A key swing factor in my outlook is the prospect for capital spending given tax reform. Surveys of businesses we've conducted suggest that capital expenditures will not grow explosively. Recent data potentially point to a stronger response, especially among tech firms. This represents an upside risk to our outlook.

As I've noted in previous speeches, an additional downside risk is the uncertainty about changes in trade policy.

Pondering a different framework

In the context of this outlook, I'd now like to tackle a fundamental question: Is the current monetary policy framework—one that targets a 2 percent inflation rate—still the best one? Over the course of roughly two decades prior to the global financial crisis, most monetary-policy experts and practitioners concurred that something like 2 percent is an appropriate goal—maybe even an optimal goal—for central banks to pursue. So why rethink that target now?

The answer to that question starts with another consensus that has emerged in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. There is now a widespread belief that, once monetary policy has fully normalized, the federal funds rate—the FOMC's reference policy rate—will settle at a level significantly below historical norms.

I like to think in terms of the "neutral" rate of interest—that is, the level of the policy rate that is consistent with the FOMC meeting its longer-run goals of price stability and maximum sustainable growth. In other words, it's the level of the federal funds rate consistent with 2 percent inflation, the unemployment rate at its sustainable level, and real GDP at its potential. Estimates of the neutral policy rate are subject to debate. But a reasonable notion can be gleaned from the range of projections for the long-run federal funds rate reported in the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) after the March FOMC meeting. According to the latest SEP, neutral would be in a range of 2.3 to 3.5 percent.

Here is the upshot: in the latter half of the 1990s, as the 2 percent inflation consensus was solidifying, the neutral federal funds rate would have been pegged in a range of something like 4.0 to 5.0 percent, much higher than the range considered to be neutral today. The implication for monetary policy is clear. If interest rates settle out at levels that are historically low, there will be a more limited scope for cutting rates in the event of a significant economic downturn. Even relatively modest downturns are likely to yield policy reactions that drive the federal funds rate to zero, as happened in the Great Recession.

This is where challenge to the 2 percent inflation target enters. The neutral rate I have been describing is a nominal rate. It is roughly the sum of an inflation-adjusted real rate—determined by fundamental saving and investment decisions in the global economy—and the rate of inflation. The downward drift in this neutral rate is attributable to a downward drift in the inflation-adjusted real rate. This has been documented by a lot of research—one influential entry being the work by soon-to-be New York Fed president John Williams and Thomas Laubach, the head of the Monetary Affairs Division at the Board of Governors.

And there is the essence of the argument. If the real rate of interest is governed by factors outside the central bank's control and is likely to remain low, then giving the central bank enough room to fight even run-of-the-mill downturns in the economy requires boosting the nominal rate of interest.

There are a number of different strategies the Fed could use to raise the nominal rate of interest. These include raising the FOMC's longer-run inflation target, targeting nominal GDP growth, adopting flexible inflation targets that are adjusted based on the state of the economy, and price-level targeting. While each of these strategies carries with it its own laundry list of pros and cons, I find myself drawn to a policy framework that has a version of price-level targeting at its center. Why?

Why price-level targeting?

First, I think the Fed's commitment to the long-run 2 percent objective has served the country well. I recognize that the commitment part of that sentence may be more important than the specific 2 percent target value. But, credibility and commitment imply objectives that are changed infrequently and only with a clear consensus on a better course.

Second, former Fed chair Alan Greenspan offered a well-known definition of what it means for a central bank to succeed on a charge to deliver price stability. He suggested that the goal of price stability is met when households and business ignore inflation when making key economic decisions that affect their financial futures.

I agree with the Greenspan definition, and I believe that the 2 percent inflation objective has helped us meet that criterion. But I don't think we have met this definition just because 2 percent is a sufficiently low rate of inflation. I think it's also critical that deviations of prices away from a path implied by an average inflation rate of 2 percent have been relatively small in our country.

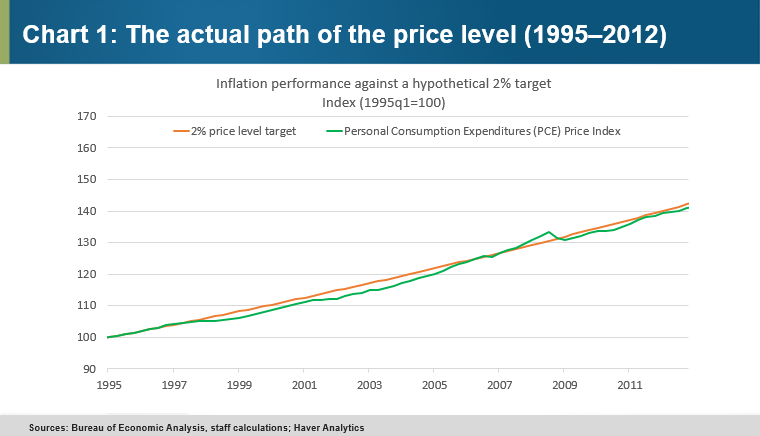

Until recently, the 2 percent inflation objective in the United States has been functionally equivalent to a price-level target centered on a 2 percent growth path. The following chart shows what a 2 percent growth price-level path would have been from 1995 to 2012. I chose 1995 to start, as that is arguably near the date when the Fed began the era of inflation targeting in practice.

The policy outcomes we have seen from 1995 to 2012 satisfy what I will call the "principle of bounded nominal uncertainty." This means that if you and I enter a contract to exchange a dollar at some future date, we can confidently predict within some range the purchasing power that dollar will represent. For me, this is the essence of a reasonable definition of price stability. It's another way to represent the Greenspan idea.

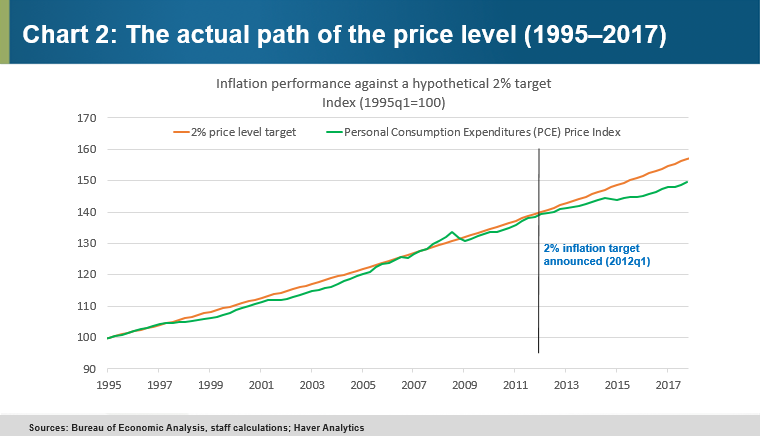

However, as I mentioned earlier, since we began explicitly targeting a 2 percent inflation rate in 2012, the actual PCE inflation rate has persistently fallen short of the 2 percent goal. That, of course, means that the price level has fallen increasingly short of a referenced 2 percent path, as shown in this chart.

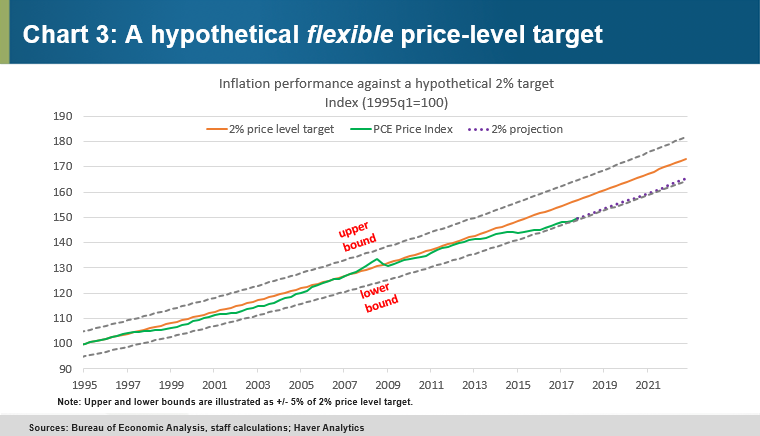

In the context of price-level targeting, how significant of an issue is this recent (and persistent) shortfall in inflation? The practical answer to that question is an implementation issue. However, for argument's sake, let's suppose that the FOMC commits to conducting monetary policy so that the price level will always fall within plus-or-minus 5 percent of the long-run target path (which itself we define as the path implied by a constant 2 percent inflation rate). In that sense, the current price level would be within the bounds of a hypothetical commitment made in 1995. If the central bank could perpetually deliver 2 percent annual inflation, that promise would remain intact, as we see in this chart.

Of course, that picture depicts a forward path for prices whose margin for error is quite slim. Continued inflation below 2 percent would, in short order, push the price level below the lower bound, likely requiring a relatively accommodative monetary policy stance—that is, if policymakers sought to satisfy a commitment to this framework's definition of price stability.

Central bankers in risk management mode might opt for policies designed to deliberately move the price level toward the 2 percent average inflation midpoint in cases where the price level moves too close for the Committee's comfort to one of the bounds (as, perhaps, in the last chart). It bears noting that in such cases there are a wide range of options available to policymakers with respect to the timing and pace of that adjustment.

This scenario illustrates the flexibility of the price-level targeting framework I'm describing. I think it's important to think in terms of gradual adjustments that don't risk whipsawing the economy or force the central bank to be overly precise in its short-run influence on inflation and economic activity. A key feature of such a policy framework includes considerable short- and medium-run flexibility in inflation outcomes. The only caveat is that deviations from 2 percent cannot be so large and persistent that they push the price level outside the target bounds.

The crux of my argument is that a "good" monetary policy framework limits the degree of uncertainty associated with contracts involving transfers of dollars over time. In limiting uncertainty, monetary policy contributes to economic efficiency.

And, as to the problem of the zero lower bound that makes further rate cuts infeasible, nothing in the notion of a price-level target rules out (or demands) any particular policy tool. If anything, bounded price-level targets could expand the existing toolkit. They certainly do not constrain it.

Summing all of this up, then—to me, the important characteristic of a sound monetary policy framework is that it provides a credible nominal anchor while maintaining flexibility to address changing circumstances. I think some form of flexible price-level targeting can be a part of such a framework.