"The ultimate purpose of financial stabilization, of course, was to restore the normal flow of credit, which had been severely disrupted. The Federal Reserve did its part by creating new lending programs to support the functioning of some key credit markets, such as the market for commercial paper—which is used to finance businesses' day-to-day operations—and the market for asset-backed securities—which helps sustain the flow of funding for auto loans, small-business loans, student loans, and many other forms of credit; and we continued to ensure that financial institutions had adequate access to liquidity."

—Chairman Ben Bernanke, November 16, 20091

Well-functioning credit markets are essential to support healthy growth in the economy. By connecting lenders with borrowers, credit markets allow households to smooth out their consumption and savings and help businesses fund their investment and operations. In particular, credit helps to smooth temporary disruptions in consumption, savings, and investment during economic downturns when household income is declining. In an ideal world, low-income and moderate-income (LMI) households would have access to safe and sound institutions that could provide reliable, affordable access to credit and opportunities for saving. Unfortunately, as Fed Governor Sarah Bloom Raskin pointed out in a speech in March 2013, "many working Americans have no practical access to reasonably priced financial products with safe features, much less the kind of safe and fair credit that is available to wealthier consumers."

|

To learn more about other studies in the Atlanta Fed Community Indicators Project, see "Taking the Pulse of Regional Low-Wage Workers" and read "Will the Housing Market Recovery Leave the Hardest-Hit Neighborhoods Behind?" |

Although most Americans use credit cards for daily transactions, many among the LMI population engage more in cash-based transactions and may not qualify for credit cards due to a lack of or poor credit history. According to the 2011 FDIC National Survey on Unbanked and Underbanked Households, a significant number of LMI families have become—or are at risk of becoming—financially marginalized. One in four families in low-income groups is unbanked, and among moderate-income families, 13 percent report being unbanked and almost 24 percent are underbanked. The lack of a relationship with traditional financial service providers and the general use of cash for transactions might be factors that encourage LMI families to seek alternative financial service providers to meet their financial needs.

In this round of the Community Indicators Project (CIP), the Atlanta Fed's Community and Economic Development (CED) team focused on learning about the trends and conditions of access to consumer credit in the Southeast.2 The CED group conducted a poll and listening sessions with consumer credit counselors, financial planners, debt managers, and other professionals in November 2012. The questions focused on three types of credit: auto loans, credit cards/revolving credit, and small dollar loans.3 This CIP article includes an analysis of the poll results along with qualitative information from our listening sessions. It also discusses the latest statistics and researchers' and community advocates' feedback.

The main results of this project indicate that consumers seek credit cards and small dollar loans4 to manage cash flow for daily expenses, health care expenses, and durable goods as opposed to unforeseen emergencies. As expected, our results indicate that poor credit history/low credit scores and low income were cited as the main barriers in obtaining this credit. In LMI communities, individuals may have insufficient income or assets or too little exposure to financial services/products to meet the requirements to establish a credit history. They may also have problems with their credit history limiting them from borrowing at competitive terms; consequently, these barriers might be very difficult to overcome or take a long time to do so.

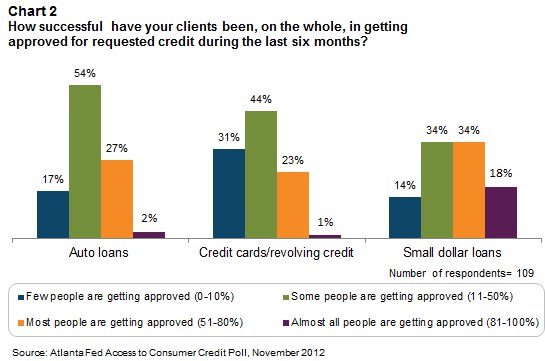

According to our respondents, credit applicants were more likely to be approved for small dollar loans than for auto loans and credit cards. A possible explanation for this result is that payday lenders charge higher interest rates than traditional financial institutions for these loans and might have fewer requirements for the loan approval.5 Lack of presence of banks in their communities or lack of access to affordable financial products are some of the factors that explain the preferential use of alternative financial services (such as payday loans, car title loans, and check cashing) among LMI households.6

Changing credit appetite

When asked about changes in interest in seeking loans in the last six months, 59 percent of respondents indicated that there was an increase in interest for small dollar loans while 19 percent saw a decline. Regarding interest for credit card loans, 45 percent of the respondents stated a decline and 34 percent indicated an increase. Finally, 41 percent of the respondents agreed that interest for auto loans has remained the same; 33 percent indicated a decline (see chart 1). The increased interest in seeking small dollar loans might be a result of the type of respondents polled; the LMI clients of credit counselors might prefer alternative financial services, thus favoring these loans. As results from the next questions will indicate, these individuals might prefer small dollar loans due to the timing of their needs, such as daily expenses, or they might have a greater likelihood of obtaining such loans versus other traditional lines of credit.

Credit to make ends meet

Respondents were asked to rank various reasons for seeking credit cards and small dollar loans in the last six months, and the most often cited were managing cash flow for daily expenses, paying health care expenses, and purchasing durable goods (see table 1). During the listening sessions, respondents also cited family emergencies and making credit card and mortgage payments as other reasons for small dollar loans. The results from the poll and listening sessions are consistent with the conclusions of the Pew study, Payday Lending in America: Who Borrows, Where They Borrow, and Why, in which survey respondents indicate that they are most often using payday loans to deal with regular, ongoing living expenses.

Participants in listening sessions also emphasized the intensive use of credit cards for daily expenses and basic needs, but the term seems to have broadened a bit.7 During the listening sessions in Atlanta and Nashville, participants agreed that the term "basic needs" includes some durable goods related to communications (e.g., cell phones). In contrast, in the economic literature, "basic needs" include food, shelter, utilities, transportation, and health care.8 However, during the listening sessions there were lengthy discussions about the role of transportation, Internet access, and mobile communication in LMI households' living standards and the impact on their ability to find and secure a job and generate income.9 For example, many job openings are only listed online and accept online applications; mobile phones are often necessary to respond to potential employer questions and offers in a timely way; or maintaining reliable transportation is critical to getting to work on time. Although one of the benefits of technology is the flow of information among individuals, for low-income families the cost of Internet access or a mobile phone has imposed an additional burden on their limited budget.

Small dollar loans are also used for daily expenses and basic needs. In our listening sessions, participants mentioned that these loans are being used by the unemployed for groceries, utilities, rent, and mortgage payments. Participants indicated that if consumers still have available credit on their credit cards, they are using cash advances to pay their daily expenses.In addition, respondents also cited family emergencies and making credit card and mortgage payments as other reasons to use small dollar loans.

In several listening sessions participants mentioned that credit cards were used to roll over existing debt or increase leverage by funding another installment payment, contributing to a debt spiral. For example, in a Knoxville session, participants mentioned the use of credit cards to pay off payday loans, utility bills, and car repairs, among other reasons. In New Orleans, participants pointed out the use of credit cards to make mortgage payments or to fund monthly expenses among the most common reasons, and the use of home equity loans for emergencies.

One of the explanations for the use of credit cards and small dollar loans for daily expenses is that many LMI households might be living paycheck to paycheck, needing financial services to solve their cash flow problems. Given their limited income, many LMI households often have few savings, leaving them unprepared for emergency expenses. According to the 2010 Board of Governor's Survey of Consumer Finances, the percentage of U.S. families with the lowest incomes (under $35,600 a year) that have savings are 32.1 and 43.9 percent for families in the lowest and second lowest quintiles, respectively. According to this survey, a family saves if they say that their expenditures are less than their total income in the last 12 months. Overall, in 2010, 52 percent of families reported that they had saved in the preceding year.10

Challenges to consumer credit access

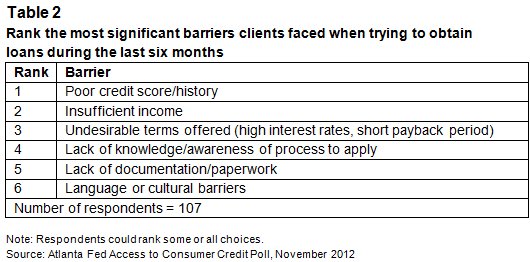

When the poll participants were asked to rank the most significant barriers affecting their clients' success in obtaining auto loans, credit cards, or small dollar loans during the last six months, they cited poor credit history, insufficient income, undesirable terms offered, and lack of knowledge/awareness of the application process as the four most significant barriers (see table 2). Economist Kelly D. Edmiston (2013) pointed out in the Kansas City Fed's LMI Survey that "the LMI population tends to have lower credit scores than average and that this hampers their ability to attain financial stability and self-sufficiency."11

During the listening sessions, participants supported these poll results and also mentioned financial regulation as a potential factor that creates additional barriers for borrowers to access these loans. Participants stated their clients' perception that more regulation resulted in additional required documentation from banks, raising the cost of credit not only in terms of fees and travel expenses to obtain these documents but also in terms of time, making potential borrowers reluctant to apply.

It is important to distinguish two types of barriers to accessing credit; one type of limitation comes from consumers' financial situation such as poor credit history, poor credit score, lack of knowledge, or cultural barriers. This situation could be the result of LMI individuals' economic constraints and/or understanding of personal financial management. The second type comes from the characteristics of the financial structure where the LMI community is located such as number of financial institutions, services, and affordability. Financial literacy programs could be one of the solutions for the former, more engagement and collaboration among community-based organizations and financial institutions a possible solution for the latter.

Credit applicant approvals

According to survey respondents, their clients were more likely to get approved for small dollar loans than auto loans and credit cards/revolving credit. In fact, most respondents said that more than half of their clients have had success getting a small dollar loan. In comparison, only about a quarter of respondents said that 50 percent or more of their clients were successful in securing auto loans and credit cards/revolving credit (see chart 2).

When asked about the sources for small dollar loans, respondents mentioned that the first source is payday lenders followed by credit unions, friends and family, and regional and community banks. For auto loans, the main source is credit unions followed by regional and community banks. According to Edmiston (2013), some LMI consumers have had more success securing traditional loans at small local banks than at national institutions.

Conclusion

The purpose of the CIP on Access to Consumer Credit was to better understand the consumers' needs for credit and their challenges in accessing financial products. According to our poll respondents, there is an increase in the appetite for loans, specifically for small dollar loans. Participants in our listening sessions mentioned a shift in consumers' attitude toward credit, pointing out that more clients are looking for opportunities to rebuild their credit history instead of taking additional credit, resulting in a growing interest in debt management and consolidation.12 However, LMI consumers are still facing challenges accessing reasonably priced credit, either due to their financial situation or because of the financial institutions and services available in their community.

Looking at the survey results leads us to more refined questions. Does improvement in economic trends, such as income and wealth, lie behind the decreased demand for some types of credit? Would further improvement spur a return to higher leverage levels for LMI households to finance education or durable goods purchases? Is this behavioral change permanent or temporary? What is the impact of small dollar products developed by credit unions and community banks on consumers' attitude toward credit? What is the impact of new products offered by online and mobile banking on consumers' credit behavior? Has financial education and more information and transparency in credit transactions had a role in consumers' credit decisions? How will consumers' attitude toward credit and debt affect their household financial stability and their ability to build wealth in the long run? What can financial service providers, community based-organizations, and researchers do to facilitate the best outcomes?

We plan to pursue some of these questions in the future in an effort to better understand the role of credit in LMI households and its contribution to economic growth.

By Myriam Quispe-Agnoli, Atlanta Fed research economist. For questions or comments please contact myriam.quispe-agnoli@atl.frb.org

The opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System. Ana Castilla, Karen Leone de Nie, Todd Greene, Janet Hamer, Anil Rupasingha, and Paula Tkac provided useful comments. Daniel Cotter and Kyungsoon Wang provided invaluable research assistance. All errors are the responsibility of the author.

Glossary

Alternative financial service provider: These providers operate outside federally insured financial institutions. Check-cashing outlets, money transmitters, car title lenders, payday loan stores, pawnshops, and rent-to-own stores are considered alternative financial service providers.13

Banked consumer: Person who has a bank account and does not use alternative financial services.14

Community Indicators Project: The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's Community and Economic Development team conducts the Community Indicators Project. The project is a systematic process to collect, analyze, and disseminate quantitative and qualitative information about low- and moderate-income communities gathered in interviews, forums, and surveys to inform policy discussions and the work plans of the Atlanta Fed and others. The project focuses on four topics: housing and neighborhood stabilization, community development nonprofit capacity, workforce development and labor force participation, and access to consumer credit.

Low-income group: Families or households that earn 50 percent or less of the area family or household median income, respectively.

Moderate-income group: Families or households that earn more than 50 percent or less than 80 percent of the family or household area median income, respectively.

Payday loans: Small-dollar, short-term unsecured loans that borrowers promise to repay out of their next paycheck or regular income payment. Payday loans are usually priced at a fixed-dollar fee, which represents the finance charge to the borrower. Because these loans have such short terms to maturity, the cost of borrowing, expressed as an annual percentage rate, can range from 300 percent to 1,000 percent or more.15

Small dollar loans: Loans of $2,500 or less. This is a broad definition that includes payday loans and other small-dollar loans. The FDIC has a Small Dollar Loan Pilot Program for loans of $2,500 or less, payable in 90 days or more, at an annual percentage rate of 36 percent or less (including origination and other fees).16

Traditional financial service provider: These are federally insured financial institutions such as commercial banks, savings institution, thrifts, and credit unions.17

Unbanked consumer: Person who does not have a checking, savings, or money market account; also, the consumer's spouse or partner does not have such an account.18

Underbanked consumer: Person who has a checking, savings, or money market account but who also has used at least one alternative financial service in the past 12 months.19

_______________________________________

1 See Chairman Bernanke's speech.

2 The Southeast refers to the Sixth District, which includes all of Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, and parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

3 Thirty-two participants attended listening sessions and interviews in Atlanta, Biloxi, Fort Lauderdale, Knoxville, Nashville, New Orleans, and Orlando. Listening session participants were largely credit counselors and financial service providers. An additional 133 professionals answered the access to consumer credit poll. The poll respondents provide credit counseling (43 percent), debt management (17 percent), or a combination of these services, including housing counseling (38 percent). Seventy-seven percent of the poll responses came from InCharge Debt Solutions (42 percent) and CredAbility (35 percent), both credit counseling agencies. The clients of the respondents are largely individuals with varying degrees of credit problems. Consequently, their answers may bias the results. The poll also included questions to identify trends and conditions related to sources and uses of credit, as well as possible barriers to accessing these loans.

4 In the poll, respondents were asked questions about small dollar loans, defined as loans of $2,500 or less. See the Glossary for the definitions of small dollar loan and payday loan.

5 For a discussion on the characteristics of payday loans see Kelly D. Edmiston, "Could Restrictions on Payday Lending Hurt Consumers?" Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, First Quarter 2011.

6For a discussion on the challenges and issues facing many unbanked and underbanked individuals and their motivations and reasons for choosing particular financial services, see Laura Choi, "From Cashing Checks to Building Assets: A Case Study of the Check Cashing/Credit Union Hybrid Service Model," Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper 2013-01, January 2013.

7 Participants in listening sessions are referring to consumers of all income levels.

8 The Cost of Living Index for Urban Areas includes these categories as basic needs plus miscellaneous goods and services. See U.S. Census Bureau Cost of Living for Urban Areas Index.

9 In "Taking the Pulse of Regional Low-Wage Workers," one of the reasons for not finding a job is spatial mismatch, where lack of transportation is a barrier to access areas with job openings.

10 See Table 1, page 8 in Jesse Bricker, Arthur B. Kennickell, Kevin B. Moore, and John Sabelhaus, "Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2007 to 2010: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances," Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Bulletin 98, No. 2, June 2012.

11 Kelly D. Edmiston, "The Low- and Moderate-Income Population in Recession and Recovery: Results from a New Survey," Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas, Economic Review, 1st Quarter 2013.

12 See a PBS report on how banks and consumers are "still cautious" on credit and debt.

13 For a detailed description of these services, see "Alternative Financial Services: A Primer," FDIC Quarterly, April 27, 2009.

14 Matthew B. Gross, Jeanne M. Hogarth, and Maximilian D. Schmeiser, "Use of Financial Services by the Unbanked and Underbanked and the Potential for Mobile Financial Services Adoption," Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Bulletin 98, No. 4, September 2012.

15 See FDIC, "Payday Lending," January 29, 2003.

16 See FDIC, "A Template for Success: The FDIC's Small-Dollar Loan Pilot Program," July 10, 2010.

17 See U.S. Attorneys' Manual, title 9, "Federally Insured Financial Institutions."

18 Gross, et al.

19 Ibid.