The relationship between labor force participation and the unemployment rate has received renewed scrutiny as the number of unemployed workers remains elevated even two years after the end of the Great Recession. The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and Conversable Economist are just a few of the media outlets that have written on the subject. Consequently, in May 2012, the Atlanta Fed's community and economic development (CED) group polled representatives of public and private organizations that provide employment, training, and social services to low-wage individuals throughout the Southeast.1 The objective was to explore the formal and informal labor force participation of low-educational-attainment and low-wage individuals. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, approximately one-third of the U.S. labor force falls into this category, including some individuals in the following occupations: construction and extraction (mining and drilling); installation, maintenance, and repair; food services; production; and transportation and material moving.2

Respondents' insights: Barriers to finding jobs

When asked about the barriers low-wage individuals face when seeking employment, skills mismatch and lack of technical skills and experience are the most significant hurdles, according to poll respondents (77 percent). That response is followed by no jobs available where applicants live or can access with existing transportation options (64 percent), and lack of soft skills such as the social skills, attitude, or appearance required by employers (55 percent).

Because earnings are highly positively correlated with education, it is instructive first to consider unemployment rates by educational attainment over time. As chart 1 shows, unemployment rates have historically been higher for individuals with a high school diploma (8.1 percent) or no high school diploma (13 percent). Furthermore, the gap between unemployment rates of college graduates and those with a high school degree or less education widened during the recession and is just starting to show preliminary signs of shrinking.

While skills mismatch, the lack of jobs, and poor social skills were top barriers to finding employment for low-wage individuals (see box below), poll respondents largely described background checks (such as driving record or credit check) and drug tests as minor barriers. Furthermore, the role of unemployment compensation to enable individuals to continue searching for more desirable jobs was not considered a major deterrent to seeking employment.

| Ranking of barriers to employment for low-wage workers | |

| 1 | Available jobs require experience, skills, or certification that individuals do not have. |

| 2 | There are no jobs nearby, or they are inaccessible by existing transportation options. |

| 3 | Workers have a lack of social skills, professional appearance, or appropriate attitude required by employers. |

| 4 | Applicants cannot pass background checks for driving record or credit check. |

| 5 | Applicants have a lack of skills or access to technology to submit job applications. |

| 6 | Applicants fail drug test. |

| 7 | Wages are not as good as unemployment benefits. |

| 8 | Employment opportunities are undesirable (shift work, weekend work, travel, physically strenuous). |

| 9 | Unemployment compensation is sufficient to enable individual to search for more desirable job. |

| Source: Atlanta Fed Poll on Low-Wage Worker Labor Force Participation, May 2012 | |

In a June 7 macroblog, Dave Altig, Atlanta Fed research director, and John Robertson, Atlanta Fed senior economist, point out that according to a separate but related poll of businesses, "the lack of technical skills is the only factor that really jumps out as an issue that businesses have with the pool of job applicants." This poll also supported the finding that drug tests were not an issue. "Only 7 percent indicated a problem with applicants passing screening requirements like drug-use or credit checks," according to the authors (see chart 2).

Respondents' insights: Reasons they quit looking for jobs

When asked about the main reasons why individuals stop looking for a job even though they would like to work, 57 percent noted that potential earnings were insufficient to pay for necessary child and elder care, and 51 percent said they became discouraged after a lengthy and unsuccessful job search.

After long stints of unemployment and job searching, there is little surprise that individuals have become increasingly discouraged, as many of the poll respondents noted (see chart 3). However, many respondents also gave reasons other than discouragement for leaving the labor force.

Julie L. Hotchkiss, an Atlanta Fed economist, used the Current Population Survey (CPS) administered by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to explore in a May 11 macroblog reasons given for nonparticipation. She finds a historically unprecedented increase in the share of labor force nonparticipants who marked "Other" as the reason for dropping out. Although she recognizes that it is difficult to interpret the rise in "Other" as a response, she says, "This category may be capturing some of the discouraged workers."

Hotchkiss also finds a significant shift toward "School" for labor force nonparticipants who are 25 to 54 (see chart 4). This finding appears to be in contrast to the poll results, which suggest that pursuing training or higher education are the least likely reasons that low-wage individuals drop out of the labor force. However, in further conversation, Hotchkiss indicates that the rise in schooling identified in macroblog is found primarily among those who have some college course work or a college degree. Together, this evidence may suggest that those individuals with less education face unique barriers to participating in training or education to elevate their skills. Additional research is needed, but it is reasonable to suggest that a lack of wealth or assets, as well as resources to provide child care and transportation, may make such pursuits very difficult for low-wage individuals.

Respondents' insights: Potential jobs in underground economy

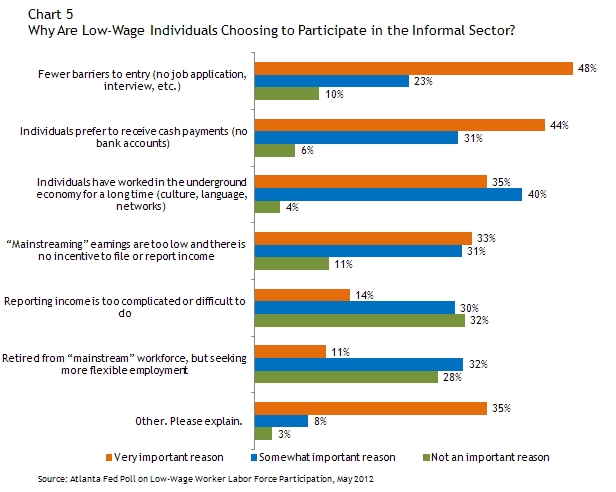

Of respondents who had knowledge of the informal sector, or underground economy, 52 percent report that it has grown in the last five years. The most important reasons that low-wage individuals participate in the informal economy are fewer barriers to entry such as no job application, interview, and so on (48 percent), preference for cash payments (44 percent), and individuals have worked in this sector a long time (35 percent). See chart 5.

Several poll respondents noted that the potential wages individuals would garner in the formal economy would be insufficient to cover household expenses, leading some low-wage individuals instead to seek opportunities in the underground economy. In doing so, they would continue to receive public assistance while also receiving unreported wage income. For example, one respondent said that any formal sector job paying under $14 per hour would result in a net income loss after accounting for the additional travel and child care costs and the resulting loss of public assistance.

In sum, the poll highlighted some key findings on low-wage individuals' participation in the labor force. Low-wage workers in the Southeast are challenged by a lack of technical education, skills, and certification required for existing job vacancies. They also have difficulty accessing jobs because of jobs-housing mismatch and a lack of soft skills. The poll also indicated that low-wage individuals stop seeking employment mainly because their potential earnings cannot cover the cost of child and elder care, and because they become discouraged after a lengthy job search.

These findings have been corroborated in the more than 25 forums and listening sessions on employment issues that the Atlanta Fed and other Federal Reserve Banks have held with workforce development professionals nationwide. Stakeholders have identified skills gaps, child care, and transportation as universal challenges for which comprehensive and coordinated responses are needed. A national report on the forums will be released later this year.

By Myriam Quispe-Agnoli, research economist, and Karen Leone de Nie, research director, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's community and economic development group

1 The Southeast refers to the Sixth Federal Reserve District, which includes all of Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, and parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee. The poll was sent directly to 418 individuals and indirectly through referrals from state agencies; 143 people completed the poll (33 percent response rate). Ten interviews were also conducted with workforce development representatives in the Southeast.

2 Low-educational attainment refers to individuals with a high school diploma or less. The median earnings of workers with a high school diploma are $26,349 (under $13 per hour for a full-time job), and with less than high school diploma, $18,413 (under $9 per hour for a full-time job)—representing 79 percent and 55 percent, respectively, of the overall median earnings of $33,298 (about $16 per hour for a full-time job).