The novel coronavirus COVID-19 is like no other challenge in recent history. The scale, speed, and comprehensiveness of the virus are unmatched by past natural disasters or economic downturns. Even in the recent Great Recession, the impact on households, workers, and businesses unfolded over months and years, rather than days and weeks.

That means there is no perfect road map to tell us how to handle a global epidemic. But a good first step is to listen and learn before working together to craft a response. Over the past few weeks, the Atlanta Fed's community and economic development (CED) program embarked on a virtual listening tour to collect real-time economic and social impacts of this public health crisis in the Southeast's underresourced communities and the organizations that serve them.1

The Atlanta Fed is already responding to what we are hearing by:

- highlighting policies that can provide quick help to COVID-affected workers and firms

- measuring childcare demands of health services workers and tracking solutions in numerous states and cities

- documenting how the newly legislated enhancements to the social safety net could financially support displaced workers.

Read on to join us at the start of a journey to share experiences, experiments, and emerging evidence that can help inform how to address the COVID-19 related economic and social challenges facing low-income communities in the Southeast.

A closer look at households and communities

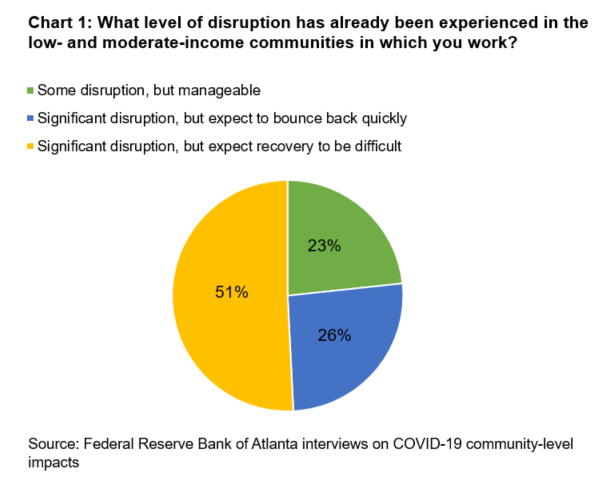

Civic leaders across the Southeast are in triage mode right now, trying to stabilize and secure essential needs first and foremost. That can be as basic as food to feed a family and as complicated as bridge loans for a small business to make payroll. The Southeast's economy has concentrations in sectors that are particularly vulnerable during this outbreak, including tourism, transportation, and oil and gas. These same industries have few workers who can work from home and limited access to paid leave. The pandemic in many ways is amplifying preexisting disparities, with 51 percent of respondents expecting for it to be hard for low- and moderate-income communities to bounce back from this crisis (see chart 1).2

Workers: Concerns about decline in wages, hours, and job loss dominated. Both small business lenders and social services contacts noted that workers from the services, hospitality, retail, and entertainment industries had already begun to feel the harsh effects of an economy that suddenly shut down. These same sectors are dominated by lower-wage workers who are at risk of living paycheck to paycheck, with little savings to rely on. For those employees who were able to work, school closures created new strains, as families chose between going to work and taking care of their children. Respondents in Florida are concerned about the temporary closure of childcare centers becoming permanent due to a decline in customers and thin operating reserves. Those who work in rural areas worried about health care access and rural hospital capacity to respond to a surge in patients absent public support, while those assisting lower-wage workers feared health care access was going to be financially out of reach, given the lack of health insurance or inability to afford co-pays and deductibles.

Respondents identified some solutions to support families' urgent need for income support. Workforce development organizations were getting ready to support the large numbers of workers filing for unemployment insurance. States like Tennessee quickly launched programs to support the rapid training and rehiring of workers from declining sectors like hospitality into “essential” industries like grocery and logistics. Some states, including Florida, support a Short-Time Compensation Program that could potentially help businesses pay wages without initiating layoffs.

Small business: Interviewees included those who offer both financing and technical assistance to small businesses. Lenders—including banks and community development financial institutions (CDFIs)—noted that a larger than anticipated number of small businesses were asking for deferrals, forbearance, or other forms of support from lenders, government agencies, and other partners. Several respondents indicated that many of the businesses they serve operate with roughly three weeks of working capital in hand and therefore could not weather the abrupt, state-mandated business closures. The small business sectors that were frequently noted as negatively affected include restaurants, hospitality, tourism, and entertainment.

Lenders had proactively set up programs to offer support to small businesses, and they were busy working through the large volume of requests. Some CDFIs viewed their programs as an interim measure that would help clients bridge to the federal or state programs likely to be initiated in response to the pandemic. Contacts raised concerns with the Small Business Administration's (SBA) track record of implementing disaster recovery loan programs, and were uncertain if SBA programs would be able to reach borrowers fast enough to provide business continuity support, especially for the smallest firms and minority-owned firms. Some respondents noted that small business borrowers cannot necessarily take on additional debt, given the tight margins they operate under even in good times and the impact that defaults would have on an owner's personal credit history. In the absence of a clear path to generate revenue, some respondents feared that many small businesses would choose to close their doors, leaving their staff to join the surge in dislocated workers.

The outlook was not all bad, however. Small businesses deemed essential were relatively insulated, and some small business owners were already pivoting their businesses to support new opportunities in the current market. Examples included local distilleries shifting to produce hand sanitizers, local food growers trying to identify new distribution channels to replace farmers markets, and hospitals hiring cleaners from the hospitality sector. Additionally, some saw SBA's suite of emergency loans from the new Paycheck Protection Program to the existing Economic Injury Disaster Loan as important sources of relief for some business owners.

Housing: Eviction and foreclosure moratoriums, coupled with several utility companies offering relief to subscribers, led multiple respondents to remark positively about the immediate-term housing stability for lower-income renters and homeowners. However, housing contacts noted that the moratoriums and payment relief options were all temporary in nature and may still result in unsustainable debt burdens for households depending on the repayment terms. Therefore, they worried about a future spike in evictions and foreclosures in the coming weeks and months. Other contacts noted that not all renters were covered by the moratoriums—many of them extended only to rental units with some form of government support—and these protection programs could be hard for renters to navigate on their own. A rise in homelessness and overcrowding among lower-income households could create a public health concern, some feared, as it would increase people's risk of exposure to the virus, and it could also increase demand for services from organizations that address homelessness.

The small investor segments of the single-family rental and multifamily markets worried some respondents. These landlords, an important source of unsubsidized affordable rental units, could themselves be unable to pay their mortgages, driving up foreclosures and adding another source of evictions and further decreasing the affordable housing supply. Housing supply concerns were also expressed by affordable housing developers, some of whom were unable to finish construction on projects or faced additional costs to implement public health safeguards at construction sites. Some noted that disruptions in local government had also caused delays in receiving permits or recording real estate transactions.

The view from the front lines of the response

An effective response and recovery to the pandemic will require coordination between state and local government, nonprofits, philanthropy, and the private sector. Nonprofit, community-based organizations, in particular, serve as important sources of information and resources at the local and neighborhood level, helping drive take-up of government and philanthropic programs.

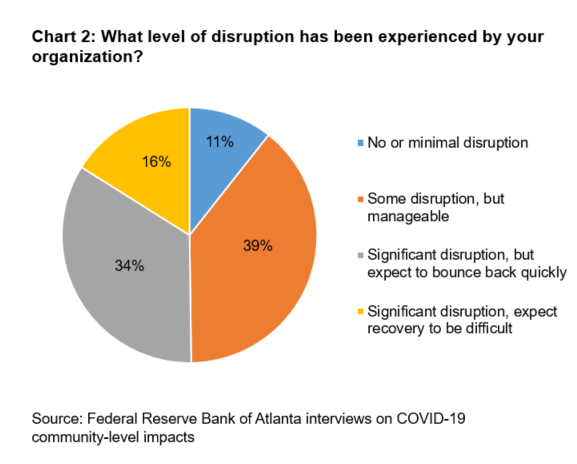

Interviewees were asked about their organization's ability to respond given the circumstances, and most respondents said the disruption had been significant (see chart 2). As mentioned above, many of the respondents were shocked by the immediate and widespread nature of the pandemic's economic impact. They contrasted it to the mortgage foreclosure crisis, noting that during the earlier crisis large numbers of families were not immediately in need of emergency assistance, and over months and years—as that crisis unfolded—nonprofits and the public sector had time to adjust their services and funding models. Going forward, the strength of the response and the recovery at the ground level will depend in large part on sustained and increasing capacity of nonprofits and governments to provide services and resources as well as targeted investments by philanthropy and business leaders.

Nonprofits: Not surprisingly, many respondents noted an increase in demand for their services. That ranged from organizations offering financial counseling, job placement services, childcare, and business or consumer credit. While most nonprofit contacts noted they were able to shift relatively seamlessly to remote services, a few contacts said the change caused financial strain at their organizations. Organizations that were dependent on volunteers found themselves particularly vulnerable and unable to deliver services, especially direct service providers that had to halt operations once social distancing mandates were enacted. This had an impact on revenues for some organizations because their public contracts required in-person delivery of services. Concerns about nonprofit revenues were expressed by not only the nonprofits but also bankers and government respondents. Some nonprofits worried that philanthropic funders would shift their support to focus on a limited set of COVID-19-related issues, or financial market uncertainty would lead to a reduction in institutional or individual donations. Spring fundraisers had been canceled, which were important sources of income for some organizations.

Regarding hiring, a few organizations had initiated layoffs or hiring freezes or had let contractors go. While some nonprofits felt confident in their ability to adapt if the crisis lasted 6 to 12 months, many more voiced doubts of their ability to endure this critical period. In addition, some philanthropic grant makers had already made general operating support grants or allowed grantees to reallocate grants to support COVID responses. Some collaborative efforts like the Greater Atlanta COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund and the New Orleans fund to support gig economy workers are working to provide grants and equity to support nonprofits and small business lenders.

State and local government: Respondents who work in or with state and local governments expressed concerns similar to nonprofits—an increased demand for services while revenues were on the decline. With the rapid rise in unemployment, respondents expressed concern that state agencies were not operationally ready to handle the large number of residents filing for unemployment or public benefits. A few respondents noted steps some state agencies had already taken to increase program participation, including eliminating job search requirements for unemployment insurance or food support recipients. Projected revenue shortfalls were exacerbated by the CARES Act-mandated changes to tax filing deadlines, increasing concerns about state budget cuts and potential funding risks for CED-related programs. For local governments, the potential loss in sales and tourism related taxes combined with deferred utility payments was leading to shortfalls in budget projections and efforts to cut back some local programs. State and local governments were trying to identify ways to get ahead of the crisis, while cities like Atlanta made emergency appropriations for food programs and small business lending.

Respondents encouraged researchers to help practitioners and policymakers identify existing public programs that could be redirected to support the newly urgent needs—whether related to jobs, small business, or housing.

Moving forward: building more resilient local economies

The past several weeks have sent economic shock waves throughout communities in the Southeast, leaving many jobless, uninsured, at the edge of insolvency, and at risk of housing insecurity. The prognosis in the Southeast remains uncertain, especially given existing health disparities and household financial fragility in the region. However, communities are already showing signs of coming together to respond. Rather than just trying to return to baseline, some want to seize this moment to foster more inclusive and equitable development practices and move toward higher-quality jobs and more effective safety nets. They hoped policymakers had learned a lesson from the Great Recession: low- and moderate-income communities take longer to rebound from events like this pandemic and therefore recovery policies need to be designed with a longer time horizon.

As the public health crisis unfolds, the Atlanta Fed's CED program remains committed to identifying opportunities to work alongside policymakers, practitioners, funders, and researchers to support the front lines in an effort to have a coordinated COVID response strategy while also promoting long-term economic mobility and resiliency in communities. If you would like to learn more or have questions, please contact Sameera Fazili at sameera.fazili@atl.frb.org, Janelle Williams at janelle.williams@atl.frb.org, or Karen Leone de Nie at karen.leonedenie@atl.frb.org.

_______________________________________

1 CED staff conducted 47 interviews between March 16 and April 1, 2020. All respondents represent organizations that serve communities in the Atlanta Fed's District, which include all of Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, and parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee. We designed the interview sample to reflect voices of people who work in housing, workforce development, small business, consumer credit, and financial counseling as well as organizations that serve both urban and rural areas. About three-quarters of respondents were nonprofits, and the remainder represented state and local government and for-profit companies. The interviews included two sets of questions on COVID-19's impact: one set about the clients served and a second set about the organization. The interviews took place just as many organizations were shifting to remote operations, and almost all occurred before the passage of the CARES Act. As a result, particularly for those respondents who are direct service providers, some were in the midst of conducting their own needs assessments of clients, while others had not yet conducted direct outreach related to the outbreak.

2 This is the first article in a series to examine challenges and show ways to implement solutions related to community and economic development amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.