Landownership and homeownership are significant contributors to the creation of wealth and thus, drivers of intergenerational economic mobility. However, many people who have inherited family land are unable to realize these opportunities because of the legal effect of their particular form of landownership, often called heirs' property. These landowners are more likely to lose their land through what is known as a partition sale—a property sale resulting from a dispute between co-owners, often ignited by an outside party with an investment interest in the land. This Partners Update article explores the repercussions of heirs' property ownership and examines legislative solutions recently enacted in three southeastern states: Florida, Mississippi, and Virginia.

The issues around heirs' property are inextricably tied to race. Accordingly, heirs' property disproportionately affects lower-wealth African Americans, particularly in the Black Belt South. Heirs' property has also contributed to the pervasive racial wealth gap in the United States. Federal Reserve research found that Black families had roughly one-tenth the median wealth of white families in 2016. Marking a bright spot in the otherwise troubling path of heirs' property, this year Florida, Mississippi, and Virginia joined Georgia and Alabama as southeastern states that have adopted the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (UPHPA), legislation that helps protect generational wealth by providing an important backstop against land loss for heirs' property owners.

Due to parallel structural discrimination that has resulted in limited health access to people of color, many of the populations most affected by heirs' property—namely, Black, Latinx, and Native Americans—have also experienced higher infection and death rates from COVID-19. The inequitable impact of a sudden and unexpected deadly pandemic combined with limited access to estate planning resources could result in a significant increase in heirs' property among these populations. In light of this possibility, the recent enactment of the UPHPA grows increasingly vital.

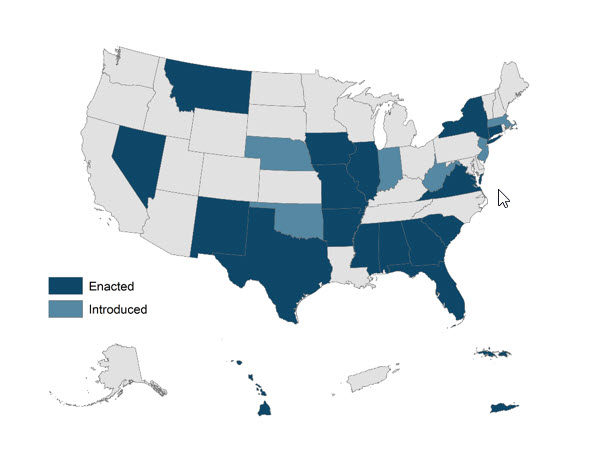

Legislative Enactment Status of the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act

Source: Authors’ own map based on Uniform Law Commission data

What is heirs' property and why does it create financial risk?

Heirs' property is most often created when a property owner passes away intestate—that is, without a legally recognized estate plan in place. The legal heirs of the deceased owner—who are determined by state law—become common owners by default (legally, "tenants in common"), each owning a fractional interest in the entire property. Heirs' property can result when a simple will bequeaths the property equally to multiple family members as tenants in common. Unfortunately, tenant-in-common ownership represents the most unstable form of common real property ownership in the United States, and the default rules often make it difficult for families to manage their property in a functional way.

In families and networks where access to affordable legal estate planning advice is limited—disproportionately Black, indigenous, and communities of color—heirs' property owners can multiply quickly across generations. There can be large numbers of owners for one tract of land, some of whom may not even know one another or know that they own anything at all. This ownership structure is unstable because a single co-tenant owner can demand their portion of the land's value by asking the courts to order a forced, so-called partition sale of the entire property. This person may be one of many heirs, or in certain cases it could be a third party who has bought an heir's interest in the property, thereby becoming a tenant in common with the co-tenants who are family members.

In addition to the risk that a relative—including but not limited to a distant relative—or an investor could force the sale of their land, heirs' property owners often lack clear, marketable title, which can reduce the amount a buyer would pay for the land and prevent an owner or buyer from accessing necessary financing. Furthermore, most loan and grant programs intended to assist low-wealth homeowners and landowners require clear title. These requirements create enormous barriers for heirs' property owners who may need help repairing their homes as they age or who may need to rebuild after a natural disaster strikes. Additionally, heirs' property can even prevent owners from deriving income from their property if they cannot get the consent of other owners.

A history of land loss

For over a century, partition sales and other questionable and even illegal practices have led to the involuntary loss of family homes and family-owned land, particularly in southeastern states. Land loss has been an ongoing issue among Black, Latinx, and indigenous people and low-income and low-wealth populations. Speculators, developers, government actors, and financial institutions have historically targeted these populations to acquire undervalued land for development. The high incidence of heirs' property among these groups, and the often-unfavorable treatment of this type of ownership by the law and the courts, renders these owners particularly vulnerable to land grabs.

In the past century, land holdings among Black Americans have fallen sharply. However, attempts to account for the volume of this loss have faced challenges. Although we do not have data to reveal the race of owners of all land types, the agricultural census data show that land ownership by Black Americans who own and operate farms has fallen from a peak of at least 16 million acres in 1910 to a low of 1.5 million acres in 1997. The data do not account for agricultural land where owners do not also operate an active farm.1 Many Black Americans own agricultural land that they rent out to others, allow to lie fallow, or use for some nonagricultural purpose. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) adjusted the 1997 estimate to 7.2 million acres in 1999 in an attempt to account for other land uses among Black agricultural landowners. A recent study points out that the USDA's estimation methods to account for agricultural land owned by Black Americans do not necessarily depict the actual on-the-ground prevalence of Black farmers and cannot be reliably compared with earlier counts.2

Just as the exact size of agricultural land loss among Black Americans is uncertain, the scope and scale of heirs' property ownership is unknown, although there are reliable estimates. A comprehensive 1980 report by the Emergency Land Fund estimated that 41 percent of Black-owned land is held as heirs' property in the Black Belt South.3 A more recent estimate suggests that 1.6 million acres in this region worth $6.6 billion is held as heirs' property.4 These figures show little sign of reversal, as less than 24 percent of Black adults have a will in place, which could prevent the formation of heirs' property.5 Other studies have found heirs' property to be prevalent among other populations and in regions with limited access to and trust in the legal systems, such as among poor white families in Appalachia,6 among Latinx families in the Texas Colonias,7 and in Native communities.8

Steps to addressing heirs' property

Thomas Mitchell—a coauthor of this article—served as the principal drafter of the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, which the Uniform Law Commission (ULC) promulgated in 2010. Mitchell began advocating for legal reforms to address problems with heirs' property ownership in 2001, when he published an article in the Northwestern University Law Review detailing the role that heirs' property ownership has played in land loss among Black Americans since Reconstruction. In that article, he proposed legislative and policy interventions to reduce loss.9 Mitchell recalls that, at the time, most legal scholars and practicing attorneys believed that due to power imbalances disfavoring those most affected by heirs' property, no state would undertake the type of legal reform he had proposed. Since then, Mitchell worked with others to persuade the ULC to draft the UPHPA, led the drafting effort, and—with the help of advocates and local coalitions across the country—ushered the resulting act into law in 17 states and the U.S. Virgin Islands (see the map).

The UPHPA includes three significant areas of reform. First, it provides that heirs who wish to retain land are able to buy out the fractional interests of heirs who petition a court for the forced sale of the property. Second, the court must consider not only the economic but also the social, cultural, and historic value of the land as well as the impact on its occupants' use of the property in the ultimate decision to sell or parcel it out. Third, in cases where physically dividing the property among the common owners is not possible and a sale is necessary, the UPHPA requires an open market sale instead of an auction, an effort to prevent land speculators from forcing partition auctions in order to acquire heirs' property for a small fraction of its value. An open market sale is substantially more likely to result in a higher sales price that benefits the heirs.

The UPHPA is not a silver bullet, but it is an important step to prevent land loss. It also provides due process for landowners who have inherited property intestate or own land as tenants in common. Recently, the ULC formed a study committee to explore ways that heirs' property owners might reorganize their interests into a more stable form of ownership. Other interventions and resources could prevent the formation of heirs' property and address the clouded title issues that inhibit heirs' ability to build wealth.

Our colleagues in the communities of advocates, service providers, and scholars who have tackled the issue of heirs' property for decades have identified a number of additional strategies such as:

- • Provide resources to facilitate estate planning, like those provided by the Center for Heirs' Property Preservation in South Carolina

- • Subsidize legal services to clear title on existing heirs' property

- • Organize and scale technical assistance programs similar to one provided by the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, to provide heirs' property owners with the tools they need to resolve title issues and improve or produce income on their land

- • Build awareness and encourage heirs' property owners to take the first step by creating a family tree, like this one provided by the Georgia Heirs' Property Law Center, to identify all heirs who may have a stake in the property. Improve record keeping and inventories of heirs' property.

Recently, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta found that up to 11 percent of residential parcels in rural areas of our district are known heirs' property, with the numbers likely much higher due to the lack of reliable data. However, current administrative practices render heirs' property very difficult to track, as county tax assessors and other entities often do not record that information. A better understanding of the location and frequency of these properties and the demographic composition of neighborhoods with disproportionately high concentrations of heirs' property would allow stakeholders to better track activity and advocate for resources.

Given the known prevalence of heirs' property—particularly among southern Black families—and the similarly disproportionate impact of COVID-19, we see Florida and Mississippi's passing of the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act as a timely opportunity. Movements like Black Lives Matter have shined a light on deep structural barriers in our society that have long prevented Black Americans from obtaining economic equity, resulting in the significant wealth gaps we see today. While this legislation will not resolve that racial wealth gap on its own, it is one of many necessary steps in what Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic has noted as a moral and economic imperative to end racism. For many families, this law will begin to balance the scales, preventing the loss of their land through partition sales and preserving the promise of intergenerational wealth that it represents.

By Thomas W. Mitchell, professor of law at Texas A&M University School of Law and the recent recipient of a MacArthur genius grant, Sarah Stein, CED adviser, and Ann Carpenter, Atlanta Fed assistant vice president. The views expressed here are the authors’ and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System. Any remaining errors are the authors’ responsibility.

_______________________________________

1 Mitchell, Thomas W. (2005). "Destabilizing the Normalization of Rural Black Land Loss: A Critical Role for Legal Empiricism." Wisconsin Law Review 2005(2), 557–615.

2 Rosenberg, Nathan and Bryce Wilson Stucki. (2019). "How USDA Distorted Data to Conceal Decades of Discrimination against Black Farmers." The Counter. https://thecounter.org/usda-black-farmers-discrimination-tom-vilsack-reparations-civil-rights/

3 Emergency Land Fund. (1980). The Impact of Heir Property on Black Rural Land Tenure in the Southeastern Region of the United States. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924067935720; Johnson Gaither, Cassandra. (2016). Have Not Our Weary Feet Come to the Place for Which Our Fathers Sighed?: Heirs' Property in the Southern United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station: https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr_srs216.pdf.

4 Bailey, Conner, Robert Zabawa, Janice Dyer, Becky Barlow, and Ntam Baharanyi. (2019). "Heirs' Property and Persistent Poverty among African Americans in the Southeastern United States." In Gaither, Cassandra J., Ann Carpenter, Tracy L. McCurty, and Sara Toering (eds.), Heirs' Property and Land Fractionation: Fostering Stable Ownership to Prevent Land Loss and Abandonment, 9–19. U.S. Forest Service. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/58543.

5 Mitchell, Thomas W. (2019). "Historic Partition Law Reform: A Game Changer for Heirs' Property Owners." In Gaither, Cassandra J., Ann Carpenter, Tracy L. McCurty, and Sara Toering (eds.), Heirs' Property and Land Fractionation: Fostering Stable Ownership to Prevent Land Loss and Abandonment, 65–82. U.S. Forest Service. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/58543.

6 Deaton, B. James, Jamie Baxter, and Carolyn S. Bratt. (2009). "Examining the Consequences and Character of "Heir Property." Ecological Economics 68, 2344–2353.

7 Ward, Peter M., Flavio de Souza, Cecelia Giusti, and Jane E. Larson. (2011). "El Título en la Mano: The Impact of Titling Programs on Low-Income Housing in Texas Colonias." Law and Social Inquiry 36(1), 1–82.

8 Kunesh, Patrice H. (Ed.) (2018). The Tribal Leaders Handbook on Homeownership. Minneapolis, MN: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Center for Indian Country Development. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/indiancountry/resources/tribal-leaders-handbook-on-homeownership.

9 Mitchell, Thomas W. (2001). "From Reconstruction to Deconstruction: Undermining Black Ownership, Political Independence, and Community through Partition Sales of Tenancy in Common Property." Legal Studies 95(2), 505–580.